Frank Gehry’s audacious and intriguing line of jewelry for Tiffany & Co. is a real exploration of forms, material and physics. Some pieces, shown above, blend together materials found in architecture such as concrete or wood with more traditional jewelry making materials, such as quartz, gold, and sterling silver. Others play with the idea of torque, and all the pieces, as Gehry is prone to do, spurn the idea of a 90-degree angle.

Frank Gehry’s audacious and intriguing line of jewelry for Tiffany & Co. is a real exploration of forms, material and physics. Some pieces, shown above, blend together materials found in architecture such as concrete or wood with more traditional jewelry making materials, such as quartz, gold, and sterling silver. Others play with the idea of torque, and all the pieces, as Gehry is prone to do, spurn the idea of a 90-degree angle.This architect-designed jewelry brought to question: Are other architects designing jewelry? Jewelry is not so far from sculpture which is not so far from architecture—the ideas of design, construction, and aesthetics are integral to all three.

Some research brought several architects from the past and present into focus.

Josef Hoffman (1870-1956), a notable architect of the Vienna Secession movement, created many beautiful brooches, shown below.

And here’s a fun one:

In 1987, Cleto Munari commissioned 16 of the world’s most renowned architects to design jewelry. It seemed impossible to track down any pictures of the works online, so after some shenanigans at the New York Public Library—the big branch at 5th Ave. and 42nd which doesn’t let you check out any of its books—the librarians chased me down the gilded halls as I was leaving dejected, thinking that I had waited an hour in vain! and put into my hands the one book with all the images I so wanted to see: Jewelry by Architects: From the Collection of Cleto Munari.

I highly recommend taking a look at the collection, even if you have to wait eons at a library to see it. The book includes the questions and answers to the same survey of questions given to each architect. They include questions like “Have you ever designed jewelry?”, “Have you ever bought a woman jewelry?”, “Do you think your jewelry is consistent with your architecture and design?”. Flipping through the book, most of the architects definitely produced works in the architectonic style and incorporated some great sculptural elements. The mark of the 80s, however, was pretty prominent, and, I have to admit, pretty funny. You can judge for yourself in some of the photos.

I do have to mention my admiration of the designs of Eisenman—they are so thought-through, like a coherent structure with systems and all. Applause.

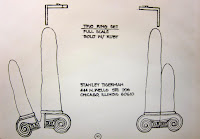

Sketches and rings by Tigerman

Necklace and earrings by Venturi

Ring by Vignelli, necklace by Zanini, bangle by Tusquets

From the Present:

Zaha Hadid (GENIUS, I do say) created some stunning jewelry with Patrik Schumacher for D. Swarovski.

“Fluid movements leading to dynamic forms, the Celeste jewellery pieces reflect the seamless complexity of the vision Zaha Hadid has explored and developed over the past three decades.

The liqueous, curvilinear shapes of the necklace and the cuff follow the formal logic of continuous transformations observed in Hadid’s morphological research.

The unique jewellery pieces are an obvious interpretation of the architectural language pursued by the practice; soft curves arise from the torso to create a dynamic form that wraps around the neck coming to rest on the shoulder eventually flowing down the arm to tentatively rest on the finger. The sculptural sensibility of the pieces is strongly accentuated by the use of sterling silver that brings to life the rhythm of folds and protrusions.

By focusing on the dichotomy between the powerful solidity of sterling silver and the organic fluidity of forms, Hadid has created exquisite, sensual and stunning pieces.

Length 43cm

Width 40 cm

Cuff

Length 45cm

Width 10 cm”

Less well-known architects have also forayed into jewelry design. Eva Eisler, who has worked as an architect, created many pieces of jewelry in simple forms that play with the idea of tension (below, left).

Design easily bleeds from one form to the other. Architects can be pretty nifty jewelry designers as well, pushing and blending the boundaries of what jewelry should and could be. I am happy to be studying architecture, but I know I’ll never give up my love of making jewelry. It's like Eisenman says, in response to the question "Do you think your jewelry is consistent with your architecture and design?": "It is my architecture, no different from my architecture."